01

01

Swimming Blind

A couple weeks in Suriname

by Nicole Smythe-Johnson

When I think about Suriname, I think about rivers. I’d seen rivers before, or I thought I had. The rivers in Suriname were not the crystal clear, blue-green tinged, pebble-lined streams I knew in Jamaica though. These were opaque and wide, chocolate milk brown or reflective black.

I was invited to go swimming on several occasions, but I could not reconcile myself to the opaque water. I met a woman who’d been attacked by piranhas some years prior. She assured me that the carnivorous fish only lived upstream in remote, heavily-forested areas. This seemed reasonable enough to everyone else, but as an island person I cannot appreciate that kind of expanse. If I am in a river and piranhas are in the river, it is too close. I cannot conceive of rivers with islands in them, rivers that have waves, rivers that are five meters deep. I have seen all of those things, but I cannot conceive of them.

I remember standing on the French Guiana side of the Marowijne River with Surinamese artist Marcel Pinas. He mentioned that the sea was not far from where we stood. I looked down the river in the direction he’d gestured, hoping for a glimpse of the sea, and asked, “Oh, really? How long would it take to get there?” He replied matter-of-factly, “Hmmm, two or three hours by boat.” I laughed and shook my head, “That is not ‘not far’ Marcel.” He didn’t reply, just looked on as if I hadn’t said anything.

02

02

Every place is different, but there was something more to Suriname’s difference for me. It was not merely unknown, but unknowable, opaque, like its rivers. It is right here, I can touch it, I can even wade in if I’m feeling courageous, but there will be no explanations. I will not see, I will not understand. I will not penetrate.

As a result, I’m uncomfortable writing about Suriname. There is a lot to say, but I’m struggling with finding a narrative that honours my thoughts and experiences. Instead of one narrative, I find myself with too many. I cannot commit to a statement, full-stopped and singular. I cannot map a totality, not even the kind of provisional totality that an essay like this requires.

***

When I called my multinational bank to tell them I was going to Suriname with a few days stop over in Trinidad, they asked me several times if Suriname was in Trinidad. The place is not only unknown to my Canadian bank – once they figured out where it was, they sheepishly confessed that my Visa card, which has served me in places as far-flung as Rwanda and Norway would not work there – the great majority of it is quite literally unknown to humans. Squeezed in between French Guiana, Guyana and Brazil, Suriname is mostly dense forest. It has the ninth smallest population density in the world.

So even though Paramaribo is a city rich in architecture and culture- the ornate, wooden, Dutch colonial style Peter and Paul Cathedral next door to the sleekly modernist Bank of Suriname is a good avatar –it seems to perch on the edge of the country. Its substantial complexity is dwarfed by the tangle of everything beyond it, in the forest, up the river.

Nonetheless, I must start somewhere, an essay about opacity would be too unsatisfying. Or would it be? Am I not free to not know? In any case, let me start with the city, get my feet wet.

Paramaribo is home to about fifty percent of Suriname’s half million people. To say the Surinamese are diverse is an understatement; they are a kaleidoscope of people, cultures, and histories that I do not feel qualified to sketch. Some stats then, the 2004 census recorded eight ethnic groups – East Indian, Creole (of African descent), Maroons, Javanese and Southeast Asians, mixed descent, Amerinidian, Chinese and white. Amerinidians can be further split into five main groups – Akurio, Arawak, Kalina, Tiriyó and Wayana. The Maroons can also be further split into six main groups – the Okanisi or Ndyuka, the Saamaka, the Paamaka, the Matawai, the Kwinti and the Aluku [1]– each with their own language, customs and even architecture. The European population is also diverse, including Dutch, Portuguese and Madeirans, as well as a substantial population of Levantines, people of the Eastern Mediterranean. The latter are mostly Lebanese Maronites and descendants of Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews. Dutch, Javanese, Caribbean Hindustani, the multiple indigenous languages spoken by the Maroons and the Amerinidians, as well as a creole language called Sranan Tongo are all spoken.

If in Puerto Rico I felt the limits of my Anglo-ness, and in Grenada, my Jamaican-ness, in Paramaribo I was paralysed by the variation. It made no sense to wish to speak Dutch, or even Sranan Tongo, if I wasn’t going to throw in Ndyuka and Saamaka and half dozen other languages. No single tongue would do. No single history would do either; it had all layered like sediment in a delta, forming a unique palimpsest of a city at the confluence of the Suriname and Commewijne Rivers.

I would have walked around just marvelling for days, had Marcel Piñas and the Tembe team not set up a brisk itinerary. It began with a visit to the Nola Hatterman Art Academy, which offers four-year art programmes for youth and adults. There, I met Surinamese artist and Edna Manley graduate Kurt Nahar, and heard about the school’s history, significance and challenges as the nation’s only dedicated art school. Kurt and Marcel both began their practices at the school, in a stately and historic, but rundown, wooden building on the banks of the Suriname River.

03

03

I then took a quick look at the pristinely white Presidential Palace and the pink-stoned Fort Zeelandia, before heading northeast across the water to the open-air museum at Fort New Amsterdam.

Wasn’t that sentence neat? Its arc smooth, like a cutlass swooping down for the chop. Do you like the tidy slice it delivered? That’s the satiny black surface of the Cottica. Someone told me it’s the deepest river in Suriname. I hear there are crocodile-like things called caimans in there, perhaps also mermaids. I haven’t seen any, but I can’t make out much.

The Presidential Palace or Gouvernementsgebouw (Dutch).

Image courtesy of Ian Mackenzie.

Fort Zeelandia (and Paramaribo) began as a trading post in 1614. The French built a wooden structure in 1640, which the British captured and fortified in 1651. The buildings that stand at Zeelandia now, however, were built in 1784, after the English and Dutch settled their quarrels with a trade of New Amsterdam in North America (which later became New York) for Suriname, then Dutch Guiana. (How uncanny that one most unknown places in the world has its origins tied to one of the most recognisable places in the world.)

Today, the fort houses the Suriname Museum. The museum was closed when I visited, so it was only on the hour-long drive over to Fort New Amsterdam that I heard that Fort Zeelandia was more than a well-preserved colonial era relic. It is also the site of a famous massacre, known in Suriname as “the December murders”. On December seventh, eighth and ninth in 1982, fifteen prominent Surinamese, who had criticised the military dictatorship then ruling Suriname, were kidnapped, tortured and assassinated at Fort Zeelandia. Apparently, the Suriname Museum tour even includes a stop at the wall bearing the bullet marks from the murder of the men; including lawyers, journalists, businessmen, a university lecturer, and two members of the military. The tale doesn’t end there however, this is not merely a dark chapter from Suriname’s recent past. Suriname’s current president, sitting since 2010, Desiré Delano "Dési" Bouterse, has been fingered as a suspect [2].

It gets quite deep here.

I knew about the civil war in the late eighties and early nineties. In a 2016 presentation at Tilting Axis 2, Marcel Pinas gave a talk about his work in Moengo, a bauxite company town in the largely Maroon Marowijne district. Pinas founded Tembe Art Studios and the Kibi Wi Koni Foundation in Moengo and developed an artistic practice that took Maroon traditions and rebuilding Maroon communities after the ravages of war as its medium. One of Pinas’ best-known works is a sculptural installation on the site of the 1986 Moiwana massacre, when the Surinamese army attacked Maroon leader Ronnie Brunswijk’s hometown. Thirty-nine people- mostly women, children and the elderly- were killed and the village destroyed.

Marcel’s presentation was what brought me to Suriname. I wanted to see his work at Tembe, but I did not connect the history that motivated his practice to contemporary politics until I got there. Bouterse was in power in 1986 as well, locked in conflict with Brunswijk, an Ndyuka Maroon who was once his personal bodyguard and a sergeant in the Surinamese army. Today, Brunswijk is leader of the General Liberation and Development Party (ABOP), which up until the last elections in 2015, were in coalition with Bouterse’s National Democratic Party (NDP). The rivals are again bedfellows, and rumours of corruption and drug trafficking swirl around them both.

It’s remarkable, but whenever I did remark on it, people were not keen to talk about it. Someone might say this or that happened before or after “the December killings” or more vaguely “after ‘82”, but little else. My guide, translator and driver, a Ndyuka Maroon in his early twenties named Dele, told me about Moengo’s glory days “before the war”, but he didn’t seem interested in discussing the war’s connection to contemporary Surinamese politics. While I was in Paramaribo, I heard about protests, but as a non-Dutch speaker, newspapers were closed to me, and when I asked, no one wanted to get into the details. They just said the protests were against the “government” or “corruption”. Its not that any one refused to talk, they just didn’t seem to think it was a terribly interesting thing to talk about. Conversations weren’t cut off, they just fell away.

This was not limited to politics. A few days after my arrival in in the city I saw what I thought was a carnival. People dressed in brightly coloured costumes were dancing and playing music in the streets. When I mentioned the festivities to Donovon Pramy, Project Coordinator at the Kibii Foundation, he said flatly, “It’s not a carnival.” When I pressed, “It looks like a carnival. What is it then?” He replied, “It’s just walking.” [3]

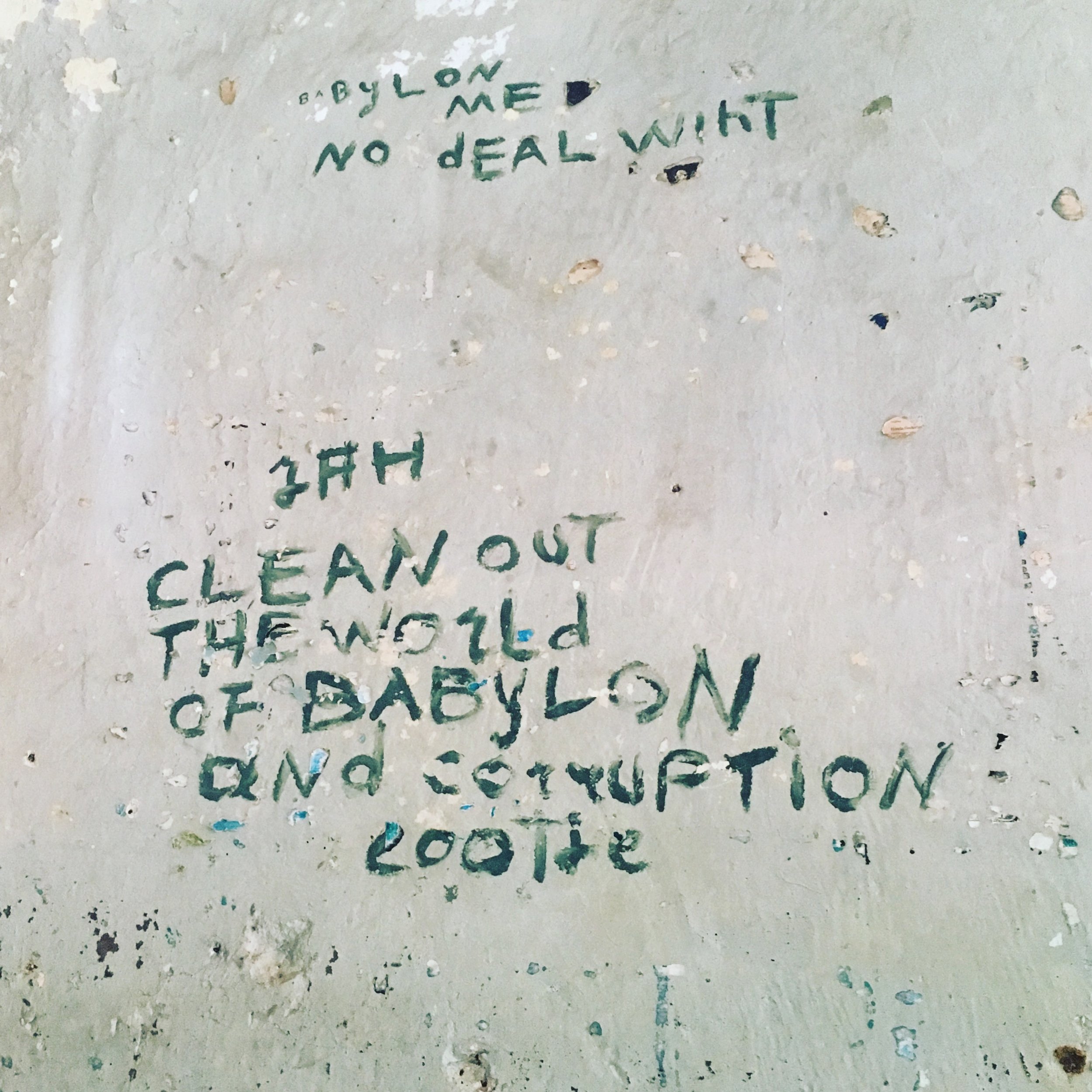

If Fort Zeelandia indexed how things began and fell apart, New Amsterdam told how things came together. Scattered across the 15 acre site are buildings, objects and plants that tell the story of early European settlement of Suriname, through the colonial period with settlers from all across Europe locked in battle with the Maroons who’d escaped slavery and formed communities in the interior. The sprawling museum park also includes replicas of traditional Saamaka and Ndyuka Maroon homes and a model of “a Javanese village” exhibiting the injustice of the indentureship agreements that brought the Javanese to Suriname with little prospect of return. The fort was also Suriname’s first prison from 1872 to 1982. Graffiti left on the wall by the prisoners is still visible, and Museum Director Marlon Madasrip explained that an exhibition called “How We Came Together Here” is planned for installation in the former cellblocks.

Does pointing out that “we came together” in a prison seem petty? According to the museum website, the exhibition would “not only [express] the ambition to show the origins of the country, but also to make the fort a meeting place for all Surinamese cultures and to continue together from there.” [4]

***

The Readytex art gallery's new building.

Political intrigue has clouded the water, but river mud has also brought fertility. The Nouhchaia family founded the Readytex Department Store in 1968. Like many Lebanese-descended Surinamese merchants, they specialised in textile and household items. In 1980, the business suffered a setback when it was looted during the military coup. Even after the debris was cleared and the shelves set to rights, it was not business as usual. With the December killings in ’82, the Dutch government ceased all development aid to the Surinamese government. Suriname had declared independence only seven years prior, and the fledgling economy, with bauxite its only real export, began to buckle under the strain. Readytex could neither get its hands on the foreign exchange needed for their import-based business, nor could they secure the appropriate licensing from the government, so out of necessity, they turned to local producers to populate the shelves

By the late eighties, Readytex’s current Managing Director Monique NouhChaia SookdewSing was out of school and ready to join the family business, and Surinamese craft had become Readytex’s niche. They sell everything from your typical souvenir t-shirts to fabric, handbags and traditional Maroon woodwork. In 1992, after requests from local artists and some prodding from long-time art lover and the family’s matriarch, Evelyne NouhChaia-Issa, art was added as a department of Readytex.

The gallery started out purchasing small pieces of artwork as stock, with larger pieces on consignment. Soon, a gallery space was designated and Readytex focused in on a group of artists that they supported in more than sales. Artists like Marcel Pinas, George Struikelblok, Kurt Nahar, and Dhiradj Ramsamoedj were able to secure advances for travel and residency opportunities on the basis of work they had in the Readytex catalogue. Artists also benefit from support with developing portfolios and artist statements, since 2005 they enjoy an online presence and archive via the Readytex Art Gallery website, and in 2006 Readytex participated in the Holland Art Fair. Readytex also supports the Sranan Art Xposed digital platform, which reports on visual art throughout Suriname in Dutch and English. The focus then, has not been exclusively selling artwork, as is the case with most commercial galleries in the region, but also supporting the development of artists’ practices.

Today, Readytex has a purpose built space for their art department around the corner from the rest of the business. There, work by the small group of artists that they represent is on display, with the first floor reserved for temporary exhibitions, usually solo shows by represented artists. Every first Thursday, they also host a regular open studio-style programme where artists can show new work and give a brief presentation on new directions in their practice. In a separate venture Monique NouhChaia and her husband have also developed a sister space called The Hall at a different site, for use by independent curators and artists. Two of the artists Readytex started out with, Marcel Pinas and George Struikelblok have also branched out and started their own initiatives.

While I did not have the chance to visit Struikelblok’s G-Art Blok, I did have the opportunity to visit Tembe Art Studios in Moengo. As I mentioned, I’d known about Marcel’s work for some time, having attended lectures by him at Tilting Axis and at his alma mater, the Edna Manley College of Visual Art in Jamaica. Having I knew that Marcel had developed an art practice that took community building and cultural preservation as its medium, but I was curious about the details. I scoured the Internet looking for context that might help me understand the why and where of Marcel’s work, both of which seemed to have far more bearing on his practice than the how. The how, if his presentations were to be trusted, was simply a matter of necessity and coherence. [5]

Just under two hours east of Paramaribo, the route to Moengo is a long, smooth road through thick bush with only an occasional scatter of buildings. As you approach the town, sculpture seems to emerge from the bush. Before you turn off the main road, before you see people, their homes and gardens, their presence is heralded by art. From Surinamese artist and former Director of the Nola Hatterman Institute Rinaldo Klas’ giant pali (a symbol representing a traditional maroon canoe paddle, and metaphor for wishes of success in future endeavours) at the entrance to Moengo, to son of soil Ken Doorson’s more modernist contribution on the side of the dirt road from the highway into town.

Much like the Moiwana memorial, nestled in dense rainforest not far from Moengo, these public artworks– created by the various artists that have done residencies at Tembe over the years– insist that something is here, was here, has been here all along. Suriname is not Paramaribo, and the rest is not just bush. This is an especially poignant message because during the civil war many Maroon villages were wiped out, including Pelgrimkondre, the village where Marcel was born. You won’t find Moiwana or Pelgrimkondre on Google Maps. An internet search might yield documentation from the 2005 petition filed with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and descriptions of the violence and trauma, but you will find no images of what was there before the village was razed. You will only understand that something was lost; you will have no inkling of what.

Much of Marcel’s, and now the Kibii Foundation’s work seems to be about filling that gap. Asserting the existence and advocating for the recognition and celebration of the Maroon culture that was deliberately mowed down not so long ago, and is still at risk of disappearing. This is in part about the legacy of the civil war, but that only exacerbated the precarious situation shared by so many traditional and indigenous communities across the Americas. The war hit Moengo and the broader Marowijne District hard, but the century-long environmental exploitation and slow but steady withdrawal of foreign bauxite companies over the last twenty years have been equally damaging for the Maroons and the Surinamese economy in general.

In a special investigative feature on American bauxite company Alcoa’s dealings in Suriname, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette journalist Len Boselovic connects Suriname to his home town:

“[T]oday, the same kind of economic trauma that distressed Pittsburgh when steel collapsed is playing out in Suriname. Alcoa’s Suriname century is ending, bringing with it a severe recession, runaway inflation and a struggle over ownership of a hydroelectric dam that provides most of this Georgia-sized country’s electricity. [6]”

This comparison could be equally well-made with Detroit or Milwaukee. Having studied in the dismally deindustrialised American Midwest, and the coal-blackened and resentful north of England, not to mention seeing the slow decay of sugar in my own country, Moengo felt familiar in all the wrong ways. As we drove through, Dele pointed out the neat concrete bungalows, once populated by middle class professionals and their families, now empty, rundown and stained bauxite red.

My spirits, high on adventure and novelty since I arrived in Suriname, began to sink. The place was heavy with “once was”, like a town that was on the main thoroughfare until a highway by-passed it. When I asked Dele if he wanted to come back and live in Moengo, he said no. If he could live anywhere it would be France, “Lots of black people there,” he said. I wanted to chide him, but how could I? I don’t live in the sugar fields of Clarendon, Jamaica as my mother had. And even though there is land there that I fantasise about turning into an off-the-grid co-op whenever modernity rubs me wrong, I live in Kingston and I travel a dozen times per year to various centres of “contemporary culture” where I buy things like kale chips and rosemary-infused castor oil, never mind that castor probably comes from quite near the canepiece of my mother’s youth. “Nothing is going forward in Suriname,” Dele said.

Maybe that’s true, I don’t know. Forward seems a bit unitary for a place that has a 250 cent coin. After all, is it really necessary to go forward only? Can one go forward by going back? This seems to be Marcel’s approach with the Kibii Foundation. Founded in 2009, the foundation aims to “contribute through art and culture to the development of Moengo and surrounding villages in the district [of] Marowijne.” [7] The foundation began with the Tembe Art Studio, a community art school and international artist residency, housed in a building that was once a hospital. Surinamese artists living abroad like Remy Jungerman and Charles Landvreugd, Dutch artists like Feiko Beckers and Yair Callendar, as well as artists from the Caribbean region like Barbados’ Sheena Rose and Curacaoan Yubi Kirindongo have all done residencies at Tembe. During residency periods of no less than a month, artists are required to engage the Moengo community, often through workshops with local schoolchildren, and produce a piece of work to be added to the Moengo sculpture park

The building also houses a recording studio, the Kibii Wi Koni Research centre, and the Contemporary Art Museum of Moengo (CAMM), which Marcel is always happy to say is the first contemporary art museum in Suriname. The research centre is now only a single room with a few computers, a library and projection facilities, but through partnerships with institutionally based researchers, like Dutch historian Alex van Stipriaan at Erasmus University of Rotterdam, the Foundation has corralled an impressive archive of Maroon history and contemporary activity. Marcel’s vision is to not only make research available, but to generate research through the training of locals in research and documentation methods. While I was visiting, for example, Dutch filmmaker Magda Augusteijn was leading a workshop on documentary techniques. The research centre is the first step in a long road to a university of Maroon knowledge. The concept of “Maroon knowledge” takes Pinas’s concerns beyond affirming Maroon culture as worthy of scholarship, to an affirmation of his community as agents of history, the producers and holders of knowledge that has served his community and could potentially serve others.

This is at the crux of Marcel’s personal artistic practice as well; if he can even be said to have one, since Pinas does not distinguish between his personal and community work. As Christopher Cozier has pointed out: “Pinas’ leadership and participation in the rebuilding of the community of Moengo is in itself a site-specific artwork.” So let’s rephrase, in that part of his work that is presented in museums and galleries, Pinas explicitly references maroon ideology and culture as a source of insight, redress and strength. A work like Kibi Wi Koni, exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum Scheidam in 2009, is an excellent example. Hundreds of bottles wrapped in the traditional Maroon textiles, called pangi, take the shape of an Ndyuka symbol on the floor of the gallery. Reminiscent of a crowd, their dazzingly bright colours take space and declare presence, but they also seem to guard a large, mostly black painting behind them. The wall piece, on which we catch a glimpse of more Ndyuka symbols and collaged Pangi, is obscured by black silhouettes, hanging from the top of the frame, their bodies forming chains, and their repetitition and posture reminiscent of diagrams of packed slave ships. The pangi-wrapped bottles are traditionally used for storing home-made medicines. Here, they seem to symbolise the Maroons of today, each one carrying medicine within, capable of bringing healing and recovery to their people, even as their history is effaced by multiple violences. Tembe, the hospital-cum-art school seems to be an attempt to redsicover and unravel those sacred cures.

![Inside CAMM: Kinderen Voor Kinderen [Children for Children] (2015), work by Surinamese artist Miguel Keerveld, also known as Tumpi Flow. The project was a collaboration with children at a primary school in Moengo.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55c52842e4b0ccebcdd59d06/1536960701418-F5FT2NC04LXIPU60WU2R/IMG_2560.jpg)