People Made of Paper_01

People Made of Paper_01

People Made of Paper:

How we write ourselves into being.

by Natalie Willis

—

“Do you want to hear the great voice of the oracle? The explosive voice of life?

Sit down around a table. Take a sheet of paper and boldly write down what it is you want to know. Fold the paper, pass it to your neighbor who will write an answer without reading your question. And so on.

Open the paper and read. You will hear echoes that come from very far away, farther than yourself; and you will finally have the most beautiful conversation you have ever had with anyone and with yourself.

Take a look.”

— Aime Cesaire, Suzanne Cesaire et al - “Voice of the Oracle: Surrealist Game”,

Published April 1942 in Tropiques: Surrealism in the Caribbean no. 5 (april 1942); translated by Myrna Rochester

Detail of work by Haitian artist Frantz Zephirin, part of the Christian Green Collection.

The Caribbean is made of paper people. Please allow me to explain . . . Paper has become a rather significant theme for my first two weeks as the Tilting Axis Curatorial Fellow in Austin, the apparent oasis in the racist-desert that is Texas. During my time here, looking through a thoughtfully amalgamated collection of Black diaspora art, with a heavy focus on the Caribbean, Surrealism has naturally garnered a lot of my interest too, given its deep connections to the region, but we’ll save that for another time. For now, it’s paper, the first point of call being that travel for Caribbeans is not easy as so many of us know.

“Yinna papers straight?” is the question for Bahamians, or to give the subtext to those unfamiliar, “have you (as a Caribbean person, and therefore a citizen of one of the ‘seemingly’ morally corrupt entryways of drugs, guns, and illegal people to the world) been deemed acceptable for travel to the US by the powers that be?” So from travel documents (including a note in my luggage lovingly left from TSA to inform me my things had been rifled through), to collage works, to performances with paper, to works on paper from my region that I had to travel nearly 1300 miles to get access to - paper is a mighty and significant thing indeed.

Detail from series of prints by Jamaican artist David Boxer, part of the Christian Green Collection.

When I was notified that I would be awarded the Tilting Axis Curatorial Fellowship for 2018, I admittedly broke down with reckless abandon on the phone, to the woman who would be my mentor no less - Lise Ragbir, the Director for the Art Galleries for Black Studies (AGBS) at the University of Texas at Austin (UT). Opportunities like this - forged from within the region but with the most tender tendrils reaching far and wide, culminating in the hard work that cultural agitators have been doing for decades - mean so much it is sometimes hard to fully encompass in words. It is a hopefulness that young professionals who stay or who return home scarcely allow ourselves to believe in.

The Caribbean narrative largely consists of telling people to get out of the region, that staying here only greets you with low ceilings in your career, that it is unviable and untenable to remain, that you do so at your own detriment. But this is by and large the kind of drain and defeatism, taken as a matter of fact or as default, which makes things so dishearteningly difficult. So to see our people (diaspora included) building meaningful connections, as several grass root art spaces are and indeed as Tilting Axis have done - this work shows us not only that it’s possible to make opportunities happen, but also that hope for this place is not frivolous but entirely, vitally necessary. I would spend 4 weeks in Austin on my residency with AGBS researching the incredibly thoughtful selection of work in the Christian-Green Collection to develop a proposal for an exhibition come September.

With Rudy Green and Joyce Christian (of the Christian Green Collection) being dedicated and thoughtful collectors of Caribbean and Black diaspora art, the awe-inspiringly competent and intentional team at AGBS and Black Studies at UT, and a most gracious host opening her home to me, my time in Texas started out with the best kind of feverish momentum. Truly, it’s the energy that can only be obtained from working with and learning from caring, sincere professionals, from people who helped me feel I didn’t have to translate myself or my experience to be understood in a new space. Associate Professor Cherise Smith (whose gift of her book Enacting Others would prove to be useful not only for my research in Austin but also my own sense of self), and Dr Eddie Chambers (whom I met previously when he visited Nassau for the NAGB’s collaborative exhibition with the British Council) were nothing short of gracious and giving, and it was a familiar sort of welcome - different people, different space, but ultimately we do all share the same wants as Black people trying to make sense of the space we take up in the world.

Not unlike many of my colleagues at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, the Black Studies team worked in their language and action to ensure there was a space made for the underrepresented masses as well as those of us who live in the sticky, tangled margins of Blackness. Everyone within Black Studies had vastly different backgrounds and levels of privilege, but the unifying thread was our commonalities (being Blackness and/or Caribbeanness), or a deep investment in these commonalities as histories, lived experiences, and ideas. The focus of my time would hinge on this in many ways - the idea of Blackness outside of the disjointedness of nationalist ideas or agendas, toward the roots (displaced, rhizomatic, or otherwise) of the experience that form this shared part of our collective being.

Billboard found in Austin

This importance on paper that was so indelibly inscribed on my mind during my time in Austin also signified the idea of an ability to put pen to paper, to be marked in history, or, (as we Caribbean and Black people have been trying to do for some time now) to write ourselves and our experiences in our own language. When we begin to think of the loss of written and printed material for Black peoples the world over, of records from the first forced displacement of peoples from the African continent that has left the Caribbean and it’s diaspora feeling at times so untethered, this importance is then thrown into even sharper relief. My excitement for embarking on this journey was charged with the most energy and anticipation I’ve had in a long time, but - imposter syndrome aside - it was also tinged with the slightest hint of trepidation of the place I would be going to, a sinking feeling and nagging at the back of my mind.

It’s still Texas.

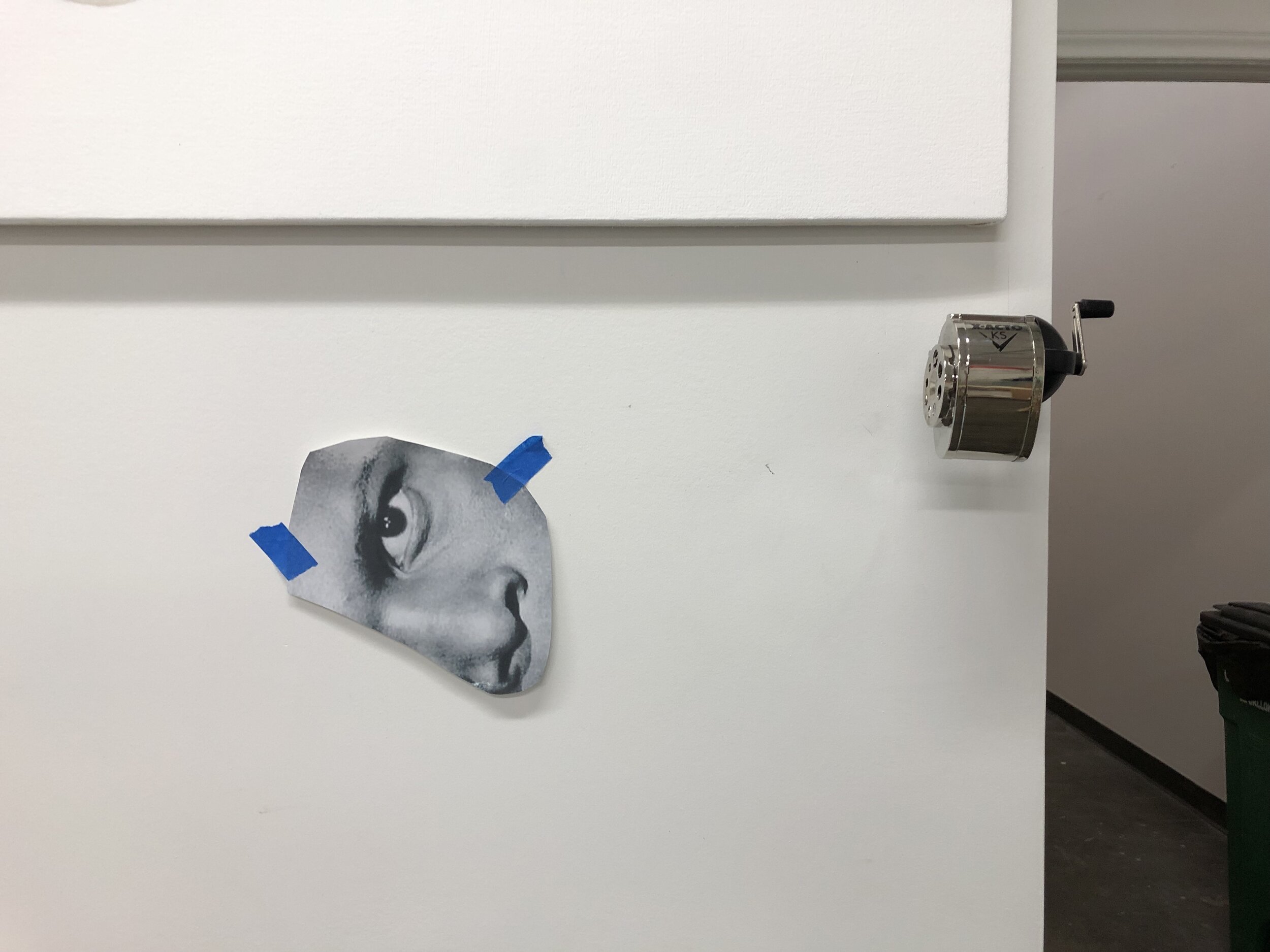

Deborah Roberts’ studio

Austin’s face, or rather it’s public-presenting self and most of its people, seem to be not just tolerant of minorities and marginalised people, but actively welcoming. I saw rainbow flags on churches, and the sense of camaraderie that I witnessed around other people of color from fellow brown folks and white folks alike pleasantly surprised me. This is of course bearing in mind that no human being should ever just be considered someone or something to tolerate to begin with, but I digress. In my experience there was also the palpable sense of an underlying tension around usage of space (for Black people in particular) and truthfully, the lack thereof.. Gentrification in Austin has gained a worryingly fast traction in the city, pushing historically Black communities further and further out from the center - though the churches remain a space to gather, to find community, to use spirit as a way to refuse to be pushed out, a sentiment that is echoed in Nassau. The latter, the tenacity of spirit and spirits, is not just something that keeps us going, or that has kept us as Black and Caribbean peoples going for centuries - it’s also embedded in the work. The map, the data, the unthinkable stacks worth of paper detailing the hows and whys, shows this economically forced migration. This is sometimes the problem with places that pride themselves on their inclusivity, on liberalism that quickly becomes lazy lip service. The issue of the “everyone’s equally special” hippie persona: it is often the work of the people in their everyday lives to be welcoming but very few do the necessary work to lobby against the systemic structural damage to marginalised people that needs to be challenged.

I was, of course a visitor there, and in acknowledging my lack of nuanced understanding that comes with being new to a place I feel it worth mentioning not only these issues around Blackness in Austin for context, but also to highlight those who make space available, especially where it is rapidly being diminished. And so, this difficult duality arises, wherein I am part of the Black community globally, but our localised experiences take precedence - so who can I possibly be to judge? Most Black people on this side of the Atlantic find that duality - of being Black on top of, or sometimes in spite of, our nationalism - is part and parcel of the experience of living in this Janus-faced world. We are not quite citizens (as women, Black people, queer people), but we can’t help but identify in some small way with the nations in which we grow up that form us simultaneously with our Blackness.

The news is terrifying for a lot of people, especially for parts of the Caribbean that tune into US news in the dystopian Trump era. The majority of the population of the planet, in fact, feels the emotional strain of the racist, misogynist, (pick your -ist), homophobic bile being supported in mainstream media - though we, the maligned majority of Black and brown and feminine bodies, might be referred to under the pseudonym of ‘minorities’ according to many newscasters. It’s a traumatising experience for Black people, for women, for Queer people - and you can be sure that if you’re any mixture thereof then you’ll feel that sense of dread every time you see the news, or very likely be moved to tears with the horror of your existence being verbally (and systemically) assaulted. I certainly do. It is an unfortunate, dystopian bingo of “which form of marginalisation will I feel attacked by in today’s Fox-Lotto?” There are, however, ways to combat this, and half of that is finding your comrades.

When you move around with your people, to your people, and to live and work among your people, that dread begins to lessen ever so slightly in the face of solidarity - despite the glorious differences we share as Black people. And ‘your people’ can be anywhere you find community, to be clear. Here is the marvelous constellation of my tribe - the art community, the Black community, the Queer community, all intersections and possibilities thereof. My experience of Texas had been a gloriously positive one, and I have no doubts in my mind that this is because I had my people, I had someone and something familiar to ease me into navigating the particularities of that very particular space. I did not move there on my own for university, I wasn’t visiting family or even long-time friends as some might, because why else might Caribbean people go to Texas of all places? I was moving to an entirely new place altogether to put up roots for a month and return home - and I felt genuinely appreciated while there.

That’s the thing really, it is always a cliché to say that Black people and Caribbean people (a space that often but doesn’t always intersect) are linked, that we have this infallible connection to others like us who live the world in Black bodies or Caribbean bodies as we do, we find a familiarity and closeness in each other. It may be that this is due in part to being in spaces that are dangerous to Black people and needing to feel safer, to feel supported - and we find ways to find home in each other, ourselves. But this is not just a stereotype, and certainly cannot afford to be. It’s the feeling that we as Black Caribbeans and African Americans may not be “sisters” per se, the differences between us is also a palpable one, but it might be more apt to say we have the same grandmother. Black people at large, Caribbean people, we are family (and truly we can fight like only family can), it’s just that we simply carry different papers.

Deborah Roberts, Political Lambs in a Wolf's World, 2018, Mixed media on paper, 108.5 x 108.5cm. Image credit: www.stephenfriedmangallery.com/artists/deborah-roberts

This is also visible in the work we produce as people of the Black diaspora, as I have been fortunate to see in my time looking at art spaces in Austin and especially in studying the Christian Green Collection. The works span across the Black diasporas of the Caribbean and the Americas, with a heavy Haitian presence, and are a justly placed point of pride for the collectors as an African American and Afro-Caribbean family. Being able to view work from across the diaspora in a single sitting feels like a luxury - but it shouldn’t, and that is an unsettling thought. For my own personal subjectivities, this is partly due to the fact that much of The Bahamas has an embarrassing frequency of anti-Haitian sentiment, in addition to an unchecked undercurrent of xenophobia generally. And so it is that many of the collections at home are lacking in representation from the rest of the Caribbean and the Black diaspora - to our own detriment and hubris as a nation. Being able to view this considered collection, as well as meet with several artists including Austin-born-and-based artist Deborah Roberts gives the lack of access we often feel in the Caribbean a slightly sharper edge in some ways. The joy in the moment is tinged with the poignant confirmation of the disparities and injustices we are working against not only in the cultural sector, but in ourselves, and it’s a blessing to have creative and cultural workers fighting this at every turn.

Deborah Roberts is as undeniable a presence in person as her work is on paper. I had my first Texas BBQ with this legend of a woman, along with Ragbir, my mentor and spirit-guide for the trip. A version of heaven exists where you get to eat the best black-pepper crusted brisket from Micklethwait’s with these two unshakeable spirits. Roberts, outside of her ever-rising global prominence, has a growing following in The Bahamas that she was pleasantly surprised to hear about, and it’s well earned esteem in these parts. She’s influencing rather a lot of creatives the world over, with her work spreading very quickly, and it really only makes sense - Black people from across the diaspora have for so long been starved of thoughtful, sincere representation. We still hear the same stereotypes being perpetuated, even with the recent appointments of politicians, contemporary artists and museum workers. Roberts’ mixed media collage and painting works take the mass-media representations of Blackness and whittle them down, stripping them of their stereotyped husks into transformed yet genuine figures and characters who despite their disjointedness feel almost heartachingly familiar. To have access to this kind of presentation of, and sincere engagement with, Blackness through the internet and through social media is key for those of us from small places - hence Roberts’ following and resonance in our space.

This reliance on the digital is not born of a vacuum of course. Most of the Caribbean does not have museums to support our own artists, let alone to house Roberts’ work, flying to the US is expensive from this space (it is a “luxury” holiday destination after all), add all this to the difficulties around securing a visa, and what we are left with then when most of us encounter work is through its widely available representation in photographs and video. All of this to say that we who live outside the centers and in the margins, those with lack of access, must find alternative strategies for building our visual literacy. This is of course true for most people, but the distance is that bit harder when you have added economic and social hurdles to climb.

Image of Sir Sidney Poitier in Deborah Roberts’ studio

Social media platforms can begin to collapse that hierarchy just a little, subvert it just ever so slightly, giving more groups of people the chance to see and be seen, to curate their own digital environments and content streams to counter the lacking narrative offered to us in other media outlets. The digital world doesn’t exist outside of our lived experience so much as it is a part of it, and despite this is it is so much more easily made malleable to our wants, desires, need to be seen for our truths. While this can spell disaster for so many, for those of us seeking sincere representation it is a godsend. There is so much potential for the Black digital diaspora to be a tool for change and for working outside of the more traditional systems of power. The internet as we currently know it is a land of pirates and the Caribbean, historically and now, has always done rather well with pirates, so I welcome it.

The synchronicities and commonalities, the sense of familiarity I found in Roberts’ studio is something quite special, I’ll call it kismet. In Roberts’ studio I saw the iconic cut outs, realistic and time-intensive painted details, and stark white canvas expected of her practice, but there were also some things that caught me off guard. For instance, I came across a cut out of Sir Sidney Poitier’s face: the first Black man to win an academy award, a Bahamian, an American too (and a family islander like myself no less), staring back at me in a way that made me feel that this moment was meant to be happening. That moment of Bahamian reach and recognition touched me, along with a collage work in progress whose working title was “Ulysses”, a profound reference the Greek Odysseus, the US President and the James Joyce literary fame, a symbol of strength.

Ulysses is also my father’s name.

Perhaps selfishly, this fellowship turned out to be not only lessons in the Black Diaspora, in Caribbean Studies, in art and curatorship, but it became deeply personal as I looked to my own identity, connections, and how even in the already-complex space the way I ambiguously present racially complicates matters further. Travel, or maybe proximity, however you want to look at it, is what brings these things to the forefront, and the end of this trip will be the longest I’ve ever stayed in the US. Plenty of time to contemplate all manner of curating and identity dilemmas, and it’s been both wild and thrilling in equal measure. The place I come from has linkages to the US, UK and the rest of the Caribbean, aligning whichever way provides the most opportune prospects at any given time - any look at how The Bahamas speaks in CARICOM meetings will tell you. It’s a sobering chance to look at my own identity and how this opportunism, unsettling as it may be, may manifest in my own way of considering myself in the world.

I also saw myself in a gallery for the first time.

I am 28 years old.

This is a problem.

People Made of Paper_02

People Made of Paper_02

Genevieve Gaignard, Drive-By, Side-Eye, 2016, Chromogenic print,

Edition of 3 + 2 AP, 24 x 36 inches

Genevieve Gaignard, not unlike myself, looks to be of a certain demographic “on paper”. We are both very light skinned (dare I say, “passing” the “brown paper bag test”), our curls don’t quite have the power to defy gravity afro-style, and our features are ambiguous. She feels eerily familiar to me, I just don’t have her added difficulty in navigating the world as a plus-size woman where the world would rather have women’s bodies diminished. Her exhibition at The University of Texas at Austin in the Christian Green Gallery (named after the collection I am digging into), titled “In Passing” speaks to this ambiguity, this state of liminality. Being light-skinned in this world is a privilege, but at the end of the day being Black in any capacity is always complicated, always varied, and being a person who is “white passing” in some spaces, but not others, problematises the essentialism of race that so many of us internalize and hold fast to. We are not merely phenotype and never have been, though it undoubtedly affects the way we move in the world. Gaignard’s playfulness in regard to how she alters and works with her racial ambiguity speaks for many like me - light-skinned Black and mixed race and with less stereotypically Black features - to the way we perform our own identity for the sake of belonging, for the sake of figuring out where we fit on the gradient in spirit and not just in skin tone.

Growing up in a predominantly Black space, as a racially ambiguous (to some) woman does things to how you see your own Blackness: it affects how you must defend it or validate it, how you’re considered Black when it’s convenient and white when it’s convenient to whichever party is the most dominant at the time. As Dr Cherise Smith, chair of the Black Studies department at UT aptly puts in “Enacting Others” (2011): “While I understand the expediency of disavowing biological determinism, I question the continued exclusion of bodies and bodily experiences from discourses of identity.” going on to share that the work in the text “aims to integrate an analysis of bodily experience into discussions of difference not as a separatist tactic but as a way to account for how difference is lived” (17, Smith). The idea of how bodily difference is lived is what felt most profound for me on personal levels. It’s a particularly potent kind of cognitive dissonance to have this kind of ambivalent sense of self as a child, and for Gaignard to have these experiences in a predominantly white space gives an entirely different experience as a racially ambiguous woman in America too, with the history of the one-drop rule still firmly rooted in place. Race for people in this liminal space can at times feels like a performance we must continue to enact over and over until we believe our own desperate need for belonging to the group we know we come from, but feel one-foot-in with. This is not universal, but I am sure it echoes for more people than just myself, especially with wider family dynamics to consider. It is not merely a performance sometimes, but a dance.

Janine Antoni in collaboration with Anna Halprin, Paper Dance, 2019 (2013). Performance view, The Contemporary Austin – Jones Center on Congress Avenue, Austin, Texas, January 24, 2019. Artwork © Janine Antoni. Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York. Image courtesy The Contemporary Austin. Photograph © Giulio Sciorio

Not unlike Janine Antoni’s collaborative “Paper Dance” series of performances with Anna Halprin at The Contemporary Austin. Antoni, the iconic feminist interdisciplinary performance artist, was born on the very same soil as myself, in the Rand Memorial Hospital on Grand Bahama Island. She grew up there, spent formative years there, and I’m sure may have felt a similar sense of dislocatedness as I have done, and as most people from my island have. Antoni is Caribbean, and though I’m in no place to confirm, she reads as white - though more often than not white families there have Black linkages down the line, because race here never was nor could be made simple. She was born in The Bahamas yes, but to parents from elsewhere in the Caribbean, and the island we both grew up on is a very particular space even within the country. Race in The Bahamas is complicated, it’s complicated everywhere of course, but how that complicatedness proliferates is different.

In The Bahamas this can change subtly from island to island, with microcultures proliferating throughout the chain of islands - and there are about 30 that are inhabited with roughly 15 or so with significant populations. In Grand Bahama, with large influxes of working and middle class white immigrants from Britain, Canada, the US, and Europe over the years, race isn’t quite as wrapped up in class for us as it is in the capital, New Providence, with their much more palpable sense of plantocracy in the contemporary. It’s not surprising, they still live amongst the physical relics of slavery and colonialism in much more seen and felt ways than Grand Bahama, whose buildings have been lost thanks to the barrage of hurricanes of the last 30 years. In Grand Bahama, whiteness is almost always considered foreign as a matter of fact, and herein lies the difficulty: how does one identify as Bahamian, when Bahamian culture is Black culture, and when whiteness is always considered to be synonymous with foreign?

Janine Antoni in collaboration with Anna Halprin, Paper Dance, 2019 (2013). Performance view, The Contemporary Austin – Jones Center on Congress Avenue, Austin, Texas, January 24, 2019. Artwork © Janine Antoni. Courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York. Image courtesy The Contemporary Austin. Photograph © Giulio Sciorio.

It’s not that there’s any lack of white Bahamian families historically living there, with their problematic and unproblematic histories. In this way, this liminal space is what made Antoni’s performances so incredibly poignant for me. Her practice opens up conversations into concepts of trace, the lived experience of the body, the feminine - both in its authenticity and the pressures placed upon us as women of all walks of life. And in this vein, the performances center on womanhood, but they also point to the lostness and desire to perform and belong that comes with being Caribbean, and further still, with being Caribbean and complicating that narrative. Rolls of light brown paper (with that particular significance for those of us from the Black community or from predominantly Black spaces), are exhausted in each of her performances. This is a work of endurance in many respects, and it shifts and changes with each new audience. Paper becomes a vehicle for Antoni to adorn, dress, sculpt, and reinscribe herself as the legion-like voices of women within the body of her practice (she makes reference to past works within her oeuvre, the audience sitting quite literally on crates of it, with select pieces set around the circle of the performance space) and within her very being itself. She problematizes the narrative with her varied background of nationalities and nationhood, with her whiteness which complicates how much she’s able to feel very much a part of a very Black place, the Caribbean, that is also her culture by birthright but is still at the end of the day just that, a Black space.

Antoni is as malleable as the paper, as we all are in the region, and especially so as women adapting to an ever-hostile world. The simultaneous strength and fragility of her working with brown rolls of paper to create sculptural forms in the most unfeigned and painfully honest and beautiful performance. We are in many respects these pieces she has torn off from the main, rolled into displaced balls flung to different corners of the space and in different times.

This performativity and displacement is part and parcel of the Caribbean experience, it’s something we cannot get away from as much as we who identify as such cannot part ourselves from our experiences of womanhood. There isn’t just a duality to this, but a multiplicity, a screaming out of many voices that speaks to the heart of what Caribbean experience is, what Black experience is, the crossover between the two. We are collectively a cacophonous choir through space and time across the globe and that is what makes this place, makes us. It’s vital essence that is so difficult to articulate, at the navel string of the Atlantic - because we are not to be articulated, we are to be gesticulated wildly, smoothly, sculpturally, ambiguously, in whatever form we deem fit, cut and paste or otherwise. It is poetry untamed because it ought not ever be contained, and we fight that history of oppression and suppression in style - Caribbean, Black, neither, all, and in-between.