New Page

New Page

A Question of Inheritance

by Natalie Willis

—

“I once heard an elder say that the dead who have no use for their words leave them as part of their children's inheritance. Proverbs, teeth suckings, obscenities, even grunts and moans once inserted in special places during conversations, all are passed along to the next heir.”

― Edwidge Danticat, The Farming of Bones

The art of keen questioning is something that could also be considered part of our patrimony as peoples of the Black diaspora, and it’s an inheritance I feel we are often not encouraged to take ownership of. It seems fitting to end my time in Texas attending a conference – a meeting of minds and kin. This is the very way that my fellowship began with its announcement at Tilting Axis last year. Edwidge Danticat, celebrated Haitian poet and keenly skilled wrangler of words, delivered a keynote address I was fortunate enough to witness in Texas that still has me reeling. Her words - in print and in flesh - had me feeling validated in the research I’ve undertaken in my time in Austin with the synchronicities that underpinned her words: conversations on spirit, ancestors, pan-Caribbeanness, the experience and longing of the Black diaspora. The University of Texas at Austin’s “Black Studies @ 50” Biennial Conference (in its second ever iteration) and Danticat’s words seem a fitting way to take up this legacy of language, of owning voices and the political power in our various individual, deeply personal ways of “being” as people. It is just that I, for one, am not very good at asking questions.

Black Studies @ 50 Conference at the University of Texas at Austin

Or, rather, I wasn’t very good at it. I think I am, slowly, learning how to get better at it, to find my own access to this heritage of criticality, of not accepting things “just because”. The creative and generative power of a well-asked, well considered question, one that thinks toward Black futures, and the subsequent aftershocks this kind of inquiry can send out into the world, are vitally necessary for Black communities and creative communities alike. They are part and parcel of what progress and resistance are made of (or what it’s many names and forms indeed require). Far from a sort of radicalness, this kind of inquiry is critical in its deepening of understanding, of helping us stretch our gray matter ever further into collectively-conscious means of analysing, exposing, picking apart the matter of life, the grayness and the visceral and the inbetween. We need to summon it all as a community of interconnected human beings.

It is also critical in the sense that this privilege of questioning is a vital part of being in the world as a people who have been handed ill-fitting and ill-fated narratives for too long - it is just that it is something I find a little elusive myself. I came into this fellowship believing I needed to have answers to any question asked, and that I was to come to Austin searching for answers on the creative culture of my African American brethren as a Black Caribbean woman. Contrary to what I thought curating was (or any kind of art or creative practice for that matter), increasingly I find it is not a practice consisting of finding answers. Instead, this fellowship has shown me that answers are useful and necessary, but that seeking delightfully well-placed queries in the wider (see: dominant) art canon is much more in line with the kind of curation I enjoy and wish to contribute to. To do otherwise can often feel inherently colonial in its propping-up and reaffirming of stereotypes, thinking that it’s easy to generalise American Blackness, Blackness as a whole, Caribbean Blackness - the nuance is so interwoven and specific the mind boggles. I hadn’t quite realised that the questions I raised in my proposal, “what is the sound of Black noise?” or “What is it to nyam on history?” - the gutteral, the ingesting and consuming of culture and heritage, was precisely what I would be required to ask of myself, the community I was being welcomed into, and the work I was seeing, over and over and over again.

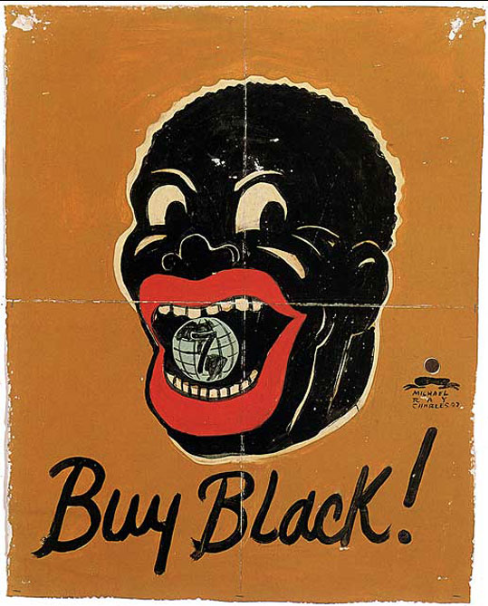

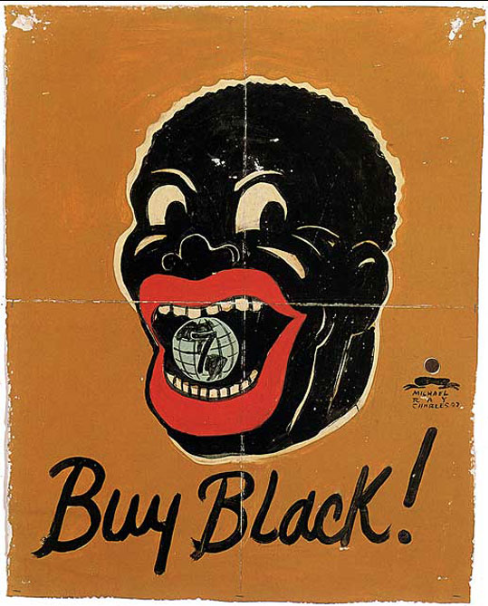

"(Forever Free) Buy Black!,"(1996), acrylic latex, stain, and copper penny on paper. Photo by Beth Phillips. Private collection. Image Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York. [https://art21.org/gallery/michael-ray-charles-artwork-survey-1990s/#3]

I battle often with the assumption that one must be seen to have the answers to everything (to anything at all, even to questions left un-asked for far too long). It has been a particularly itchy preoccupation and insecurity of mine for some time. This is not just an issue in my burgeoning and fragile career, but a wider question in life and the business of living. I believe this need to “have all the answers” - though nobody really ever asks this of us at all - is part of a greater insecurity in society, often magnified by marginalization at times. As Black and Caribbean people, as women (with the particular and often contradictory sense of simultaneous visibility and invisibility we hold), as people trying to make sense of the world, every single one of us in a non-Black or Caribbean space feel the underlying tension of having to play obliging ambassador for your race, country, gender, sexuality, experience, you name it. In The Bahamas, the Caribbean, in Texas, in our respective diasporas, we feel it. I wonder if this in part stems from centuries of Black and Brown peoples being forced to swallow a prevailing, unfair stereotype of laziness (funny, when so much free labour exploited in our histories lives on in our genes, which still remember deeply). We are people whose painful, and cringeworthy-at-best tropes are often imaged by the notion of sitting idly beneath shady trees or coconut palms, or stories of being “simple” (in the less savory sense). Of people easily placated with offerings of fruit or fried foods - as I’ve seen bitingly critiqued in the work of Michael Ray Charles in sifting through the Christian Green Collection.

As Charles demonstrates through his use of more painful and historically-rooted African-American tropes of Blackness, and as he makes us reckon with their contemporary continuations in consumer culture, we are shown the many ways that autonomy over our representation helps us see just as much what we are not as it shows us what we feel we are. We were never these stereotypes, not then and not in their contemporary aftershocks, but claiming the painful caricature as just-that helps to render it impotent as a comparison to Black people in the everyday - a reclamation through a most snarky, barking laugh in its own way. His iconic use of a single penny as a signature, the only “coloured” coin, gives both the root and the continuation of the capitalist structures that prop up these “post”-slavery, post-colonial issues. After being force-fed such sweeping generaliesations for so long (or when said force is absent and we instead must sit and stew in it as it permeates the visual culture we are exposed to day in and day out) it’s easy to see why we might feel a need at times to go above-and-beyond to provide proof of our intellectual wealth and dexterity, to fight a rising tide of implied ignorance so unfairly attributed to Blackness. The ability to sit in your knowledge, and your lack of it too, doesn’t come easy.

I just don’t come from a space that encourages questions.

“La Sirene” (nd), Myrlande Constant, vodou flag with sequins, fabric, beads, and thread, 3ft x 4ft. Part of the Christian Green Collection. Photograph by Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

But this is not and cannot be an excuse. The Bahamas isn’t particularly comfortable with the questioning of its status quo, of the “way things just are,” of our clearly dysfunctioning default - which functions just fine for upholding power to the privileged few. Of course, it isn’t just us, this is widespread and a lot of this dominant noise of the acceptance of mediocrity, and of belligerent insecurity around scarcity comes perhaps in part from the abusive history we have with one particular country in the country’s lineage - Britain. I am, complicated though my feelings may be about it, also British, and this compounds much of my difficulty in asking questions. In my experience, I’ve found much of the key linguistic heritage of Britishness in conversation to be the game of beating around the bush. To be good at implying nothing and everything simultaneously, giving no answers at all, and even better at not asking the right questions, all of it reigns supreme - just look at the rhetoric around Brexit for evidence. Brexit, far from just being what I feel in my spirit is a sort of karmic retribution for just some of the horrors of slavery and colonialism, we see the UK (and much of Europe) currently paying the price of their pretending. Pretending that the subjugation of others throughout their respective histories was acceptable - because we did of course get “railways” in India, so of course this so-called development was useful, partition and murder aside. The justification and history is made contemporary by way of reaping the ripe nationalism that has been bubbling over in this very particular way for years. The fantastically expensive farce, which reparations could never fully repay, of this false sense of reality and market born of the silencing of questions, of the impermissible impact of questioning colonial history, has come to one of its many beastly heads.

This is largely why intuitive artists (as most artists are when they begin) are so profoundly important to the wellbeing of any art ecology – but it is, in sad irony, also the reason why they are so often ostracized. This sort of practice is the life-roots of the creative community that sustain us all whilst, also somehow being the romanticised last frontier of “unadulterated” fine art creativity in some ways. Intuitive artists (because naïve art is an insult to these deeply rooted and almost decolonial ways of knowing) represent all of us. How can we know, especially in places like the Caribbean, what our art and aesthetics can (and indeed should) look like if we don’t consider those who haven’t had to translate their experience into a contemporary aesthetic at art school? How do we know what our creativity looks like when it hasn’t had to form its tongue to a language unfamiliar and niche to a privileged mouth? It’s a conversation that comes up far too often for my generation, for those of us fortunate enough to secure the ever-elusive funds to attend art school and those of us living in debts both financial and in heritage. It is, in its place outside the margins of the university, paradoxically, an important part of the decolonial work within it - providing models for those who exist in the art-wilderness outside of institution.

It is guerilla in its own way, though not immune to the prevailing colonial narratives that so many of us grow up being conditioned with. Art schools abroad, those existing outside Black-centred spaces, can have a tendency to feel elusive, elitist, and unapproachable for many of us when it comes to models for considering art practice. How can we know what Caribbean art and thought looks like when we don’t consider those who speak in art-patois? It is fighting these same colonial thoughts, but with different decolonial machinery. Despite the structure of universities fighting against programs like Black Studies, against Indigenous thought, against the rebellion of intuitive artists, it still produces the anti-colonial thinkers and movers who refuse to do so in the language of the coloniser, as paperson points out:

“Booker T. Washington’s idea of self-reliance was in no small part used to quell Black, Native, or, in the case of Kenya, Black Native unrest by developing a middle class of public servants to collaborate with the colonialist government. Yet Washington’s self-reliance also informed radical imaginations, such as Marcus Garvey’s pan-Africanism and Black economic sovereignty.” (paperson, 2017)

This history is linked in ways we can scarcely begin to put down on paper, scarcely begin to find the questions and language for. So many Black and Caribbean people (regardless of race for the latter) can be made to feel as though they must play-at-translator in university spaces to begin to understand their place in the wider canon of art, that ideas of feeling, belonging, and emotion are only acceptable insofar as they relate to Homi Bhabha and James Baldwin. It’s worth making note of, especially in considering the role of academia when it comes to marginalised peoples, as the conference for Black Studies that I attended hinges itself upon. We must make space for ourselves, and that in itself must change with new information on the nuance of Black experience in its prismed diversity. In a very similar vein, It is also worth mentioning how utterly imperative it is that initiatives like this (the Tilting Axis annual conference and now Curatorial Fellowship, like the now-bedrock that is Black Studies within academia) continue to take up space in universities and elsewhere. Coming from a region so plagued by extraction in its history and present, we can’t continue to allow not just talent, but Caribbean people the world over with their hearts and souls in this work, to feel that they have no future in their home and the landscape that is their mother and maternity. We cannot continue to orphan ourselves in spaces that don’t want us – so often academia, also the other-mother lands in Europe - because we feel that our (Black and African) mothers don’t love us. This is not to say that doing work internationally is not important, it is vitally necessary. But it can’t continue to be the case that we must travel the lengths of the globe to even begin to get information about sister-nations that are in the same waters, as I have experienced. I travelled to Texas, of all surprising places, to conduct research on Caribbean art and spirituality (most with a focus on Haitian art), simply because the space I come from is too insecure. And that insecurity manifests as the xenophobia that had cost us so much in the first place.

“Marassa” (nd), Maxon Scylla, vodou flag made with fabric, sequins, beads, and thread, 41 x 31 inches. Part of the Christian Green Collection. Photograph by Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

Edwidge Danticat, in her keynote speech at this brilliantly organized conference, rightfully mentioned the sinister role that The Bahamas – my homeland – has played in regards to the ostracization and subjugation of the people of Haiti. This was a moment of deep and well-earned shame for myself and certainly the country I come from. Danticat’s home, the place of those who “create dangerously”, is a space that Black people the world over owe a deference to: the first Black republic, won bloody at the height of colonialism and slavery by the French no less. To pay the sanguine cost of freedom and revolution in this time was unheard of, almost unspeakable, and indeed had never happened before. The intuitive artists of freedom, we have been given just one model of questioning of many, to rise above and to aim at that which seems impossible, to critique power and authority as it is handed to us neatly and arrogantly and unquestioned.

This fellowship – in all senses of the word - has been the most formative experience I could have hoped for and I am deeply humbled and indebted to the people who make moments like this happen, to the people who spoke with me, laughed with me, shared a table and shared their vulnerabilities. This thing is a family, with all the warts and joys that come with it.

This is the magic.

What I found looking through the Christian Green Collection, through artworks I now find myself coming across regularly by artists that I first happened upon in Austin, is magic, spirituality, becoming, and all of the many names connected to the great “I am” that is ancestry.

The Caribbean’s history of politics and protest and movements for the people (not just those claiming to be for people and truly being for gains of personal power), are deeply rooted in the spirituality we come from. We could not get the Rastafarian movement or the West Indies Federation without it. Because what would social justice be without an unshakeable belief in spirit? We see it in the poetic writings of Caribbean thinkers – philosophers and poets (with much interchange between the two). We are a people of strength, resilience and beauty in the muck and difficulty. This is our cultural-creole, our lingua franca, and our common tongue is as biting as it is beautiful. And I feverishly anticipate the discussions to come in Guadeloupe for the next Tilting Axis convening.

!["(Forever Free) Buy Black!,"(1996), acrylic latex, stain, and copper penny on paper. Photo by Beth Phillips. Private collection. Image Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York. [https://art21.org/gallery/michael-ray-charles-artwork-survey-1990s/#3]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55c52842e4b0ccebcdd59d06/1577073282539-LNG9GTLJJ6K1TESZHNY6/2_michael_ray_charles+.png)