01

01

Getting Located:

Three Weeks in Grenada

by Nicole Smythe-Johnson

As a Jamaican, one feels a priori entitled to Caribbean-ness. There’s a sense that “we are the Caribbean”. Even the other islands—their tourist shops filled with Bob Marley tote bags and “no problem mon” mugs—know it. When people think “Caribbean”, they think “Jamaica”. [1] I’m not trying to start a fight here. I’m just owning privilege, locating myself and being clear about my blind spots.

When I set out to travel the Caribbean then, I was a little too sure of myself. I knew I’d encounter new and surprising things, one always does in travel, but I thought I’d recognise more than I did. I thought I’d know more codes than I did. And I lost a little skin over it, because as I’ve told foreigners, so many times, “we are not all the same”. It’s hard to become the foreigner. It’s hard to accept the full weight of your un-knowing. Especially when you’re from a place that tourists routinely inundate, so that there’s a righteous edge to your claim of local-ness.

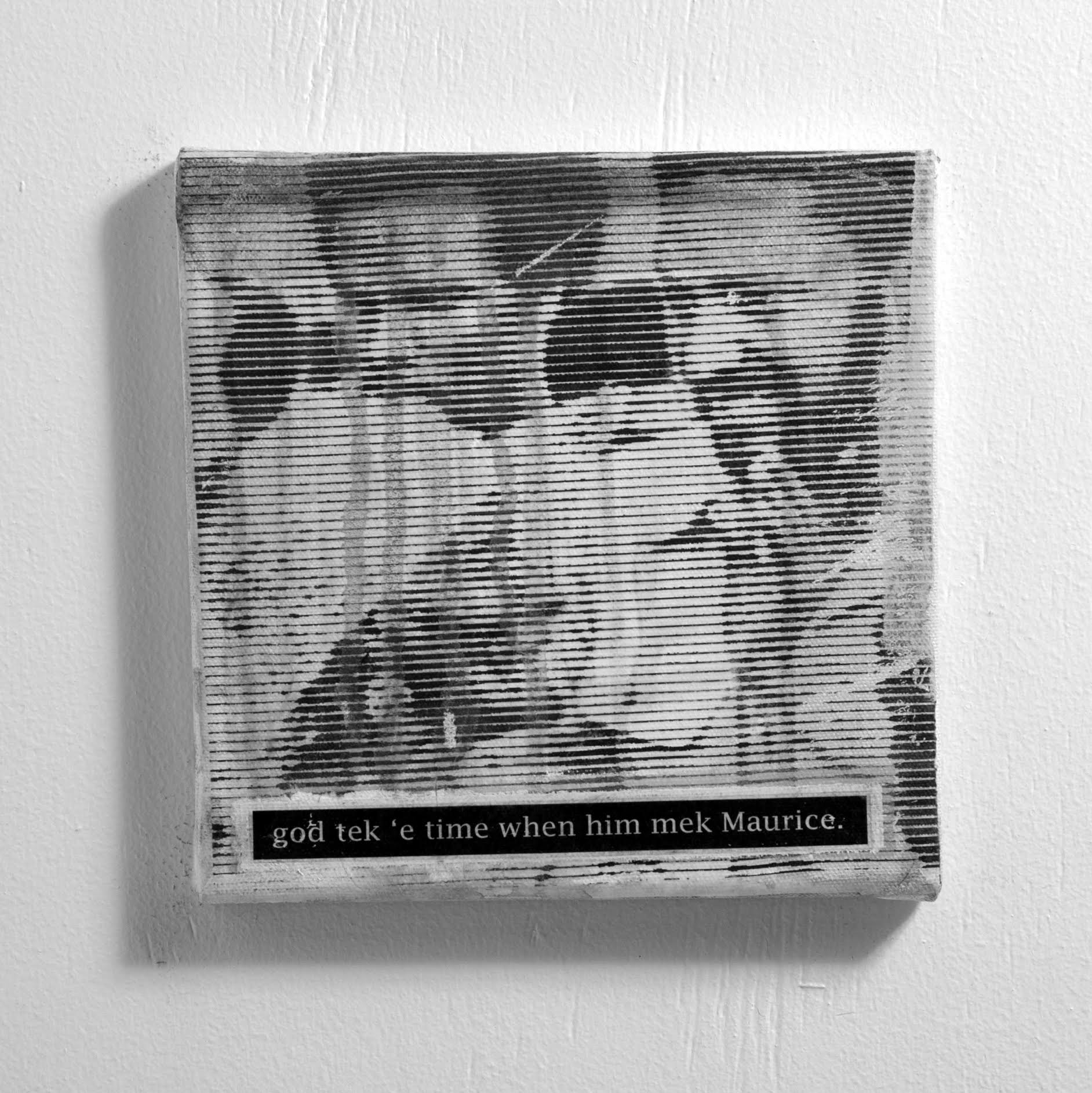

To my mind, I knew Grenada. I’d never been, but growing up on the University of the West Indies Mona campus, the tiny island state had become iconic of radical political activity in the English-speaking Caribbean. I knew about the revolution (1979-1983), the dashing Maurice Bishop. I’d been to the panel discussions, seen how even decades later they still devolved into finger-pointing indignation and charges of treachery. I had family that had lived in Grenada, friends from there. I’d eaten the exquisite chocolate, used the famous nutmeg pain-relieving spray. I knew Grenada.

What’s more, I’d often heard that Grenada was very similar to Jamaica. And it was, in some ways. In terms of landscape, Grenada is more like Jamaica than anywhere I’ve ever been, like my favourite parts of Jamaica anyway. The island is jewel green and mountainous with narrow roads that wind along contour lines. I felt “at home”—but not my everyday home in Kingston, stay-cation home, weekend-in-the-countryside home. So the familiarity was there, but not that of a local, that of a holiday-maker, what Jamaicans call a dry land tourist. [2]

02

02

“. . . its not Rasta, its the Grenadian flag. I felt foolish, tourist foolish.”

The red, green and gold only added to a growing sense of the uncanny. On my first day I went for a drive with my host, co-founder of Groundation, Malaika Brooks Smith Lowe. All along the road there were walls, rocks, curbs painted red, green and yellow. At first, that seemed natural. It would be in Jamaica, Rastas of course. It wasn’t until Malaika said, “It was just Independence day, so everything is decorated in Grenadian colours” that I realised its not Rasta, its the Grenadian flag. I felt foolish, tourist foolish.

I remember regular (often joking, sometimes very serious) charges of “Jamaican cultural imperialism” in my American college’s Caribbean Students’ Association meetings. It was part of my motivation for applying for the Tilting Axis Fellowship, exploring the way Jamaican (cultural) hegemony within the English-speaking Caribbean might blinder my breadth as a “Caribbean thinker” (whatever that might mean). I’d often rolled my eyes at visiting curators who seemed to confuse their work trip to the Caribbean with a vacation. Or the ones too busy looking for what they expected to find, to engage what they were in fact encountering. Yet here I was, foolish by my own standards, thinking all the foreign curator things.

There were also the kites. In much of the Caribbean it is customary to fly kites around Easter; it tends to be windier at that time of year, though some also argue for a symbolic connection between kites and Christ’s resurrection. In the Southern Caribbean there’s an additional element though, and I’d heard about this but I didn’t understand it until I spent two weeks living on a hill in St David’s (about half hour east of the capital, St George’s). In addition to your standard kite flying, which makes a gentle flapping noise if any at all, Grenadian fliers do not land their kites when they’re done for the day, instead they tie them to tree limbs and the kites continue to fly from that anchor for days. They add a little flap of paper to the nose of the kite (Grenadians call it the “mad-bull”) that flaps in the wind, making the strangest noise; a whirring sound that I’ve heard people from the Southern Caribbean liken to a mosquito flying right by your ear. I didn’t find it quite that annoying, but then I don’t have to live with it. I’ve never heard that sound in Jamaica; I don’t think we have that tradition. The first time I heard it, I thought it was chanting. That would be the likely explanation in the hills of Jamaica, just your run of the mill natural mystic blowing through the air. I kept asking, “what’s that noise?” To which everyone would reply, “what noise?” It took a few days to bridge the gap.

“In a way, Grenada looking like Jamaica was part of the difficulty. It looked so much like home that I couldn’t get used to the idea that it was as safe as I was assured it was.”

There were other more practical confusions. Transport was an ongoing trial. Public transport is good around St George’s and Grand Anse, but not outside that. Elsewhere, buses were unscheduled and infrequent, especially on weekends and at night. So that even if I did brave the quiet, largely bush-lined, tree-canopied dirt road, with the barking dogs that rush at you teeth-bared, I’d wait at the bus stop on the main road for an unknowable period. It was worse if you got home after sundown at around six, since the road was not lit for a good stretch. In a way, Grenada looking like Jamaica was part of the difficulty. It looked so much like home that I couldn’t get used to the idea that it was as safe as I was assured it was. “Lone woman walking on a dark country road” sounded like the opening line of a suspense thriller screenplay to me. Yet, no one seemed to share my anxiety about the dogs, or the possibility of being brutally murdered and buried in the bush somewhere.

On my hosts’ advice, I made a few attempts, but my body betrayed me. I could not keep my heart rate even, or stop my palms from sweating. My eyes seemed to dart over my shoulder of their own accord. It’s the point at which “street smarts” become an auto-immune disorder. It didn’t seem worth fighting to over-ride what Jamaicans euphemistically call “safety-consciousness” either, I would be headed back to Kingston soon enough. Grenadian taxis are London black cab expensive. And though many Grenadians hitchhike, my safety-conscious body would not be won over on that point either. So for my last week I migrated to Grand Anse. Accommodation in the touristy area just south of St George’s strained the budget, but I could get to and from town by bus within 15 to 20 minutes, even on a Sunday. The ease of movement, and the familiarity of (relatively) busy, well-lit streets made all the difference.

Navigating the “art scene” required similar adjustments. Before I arrived, I revisited a presentation I gave in Glasgow, thinking it might serve as a skeleton for a presentation in Grenada, but within days I could tell I would need to go back to the drawing board. I’d spent a month in Scotland thinking about whether that context could yield any insights relevant to the relatively under-resourced Caribbean contexts I’ve worked in (Kingston, Port-of-Spain, Nassau). My Grenada trip made me wonder how relevant a Jamaican or Trinidadian context could be for Grenada, or St. Vincent and the Grenadines, or St Kitts. I could not find a way in; no cafes frequented by “creative types”, few galleries (and those that existed seemed geared toward tourists and ex-pats). Grenada put my thesis to the test. Is there an artistic community without dedicated “spaces”, does a “scene” exist even if I cannot perceive its nodes? What is the architecture of that network-community and how might a curator engage its by-ways.

I was heartened to find that Groundation was asking the same questions. Founded in 2009 by yoga therapist and artist Malaika Brooks Smith Lowe and human rights lawyer Richie Maitland, the organisation describes itself as “a social action collective [that] focuses on the use of creative media to assess the needs of our communities, raise consciousness and act to create positive radical growth.” [3] Since then, they’ve established a board of collaborators- which includes Feminist Labour Advocate, Kimalee Phillip and Youth and Literacy Advocate, Ayisha John- and piloted several projects that straddle creative practice and social justice.

In 2013, they partnered with author Oonya Kempadoo and the Mt. Zion Full Gospel Revival Ministry to found the Mount Zion Community Library, a response to the closure of the Grenada National Library. The National Library was housed in an eighteenth century building on the Carenage waterfront in St George’s that deteriorated so badly it became unsafe for use and was closed in 2011. The library also houses the national archives, which remain in the building at considerable risk.

Groundation is known for their LGBTQ activism, so a “Gospel Revival Ministry” seemed an odd bedfellow. According to Groundation board member Ayisha John, it was Oonya Kempadoo who connected Groundation with Pastor Clifford John and Cessell Greenidge, founders of Mount Zion Full Gospel Revival Ministry. For the first few years, the church donated space in their building for use by the library. The project has since been handed over to it’s own dedicated board, moved to a larger space, and renamed The Grenada Community Library.

In 2014, Groundation also collaborated with ARC Magazine on Forgetting is not an Option, a “collaborative cultural memory project” aiming to develop and archive creative work about the Grenadian Revolution. The programme included a four-day programme of panels on art and activism, a film night, and art and creative writing workshops. In 2015 they launched their Discrimination is Discrimination project, a series of posters featuring homophobic dancehall and soca music lyrics adjusted to target another group- Rastas, Black or Indian people etc.

In October 2015 they worked with GRENCHAP (Grenada’s chapter of the Caribbean HIV/AIDS Partnership) to make a presentation on behalf of the islands’ LGBTI community at a hearing of the Inter American Commission on Human Rights in Washington DC.

After the disappointing loss of a grant in 2016—due to the islands’ banks refusal to do business with the relatively controversial organisation, leaving them without a bank account and formal financial infrastructure—Groundation was pausing to re-assess their direction. In particular, they were trying to get a realistic picture of their context and their place within it. Who are they serving? Why? How?

I became a sounding board for that process. I indulged my amateurism, carefully noting my confusions and misconceptions, and sharing them with the Groundation team as a way to expand my knowledge while sharing my enthusiasm and sense of possibility: a luxury of the fresh-eyed and bushy-tailed. I also met with a number artists and writers to talk with them about their sense of the Grenadian arts landscape.

“. . . everyone lamented a lack of peers, a feeling of isolation in their practices.”

A recurring theme in all my discussions was the lack of an “artistic community”. Though Groundation provided me with a list of recommendations of people to meet, and many of those people referred me to other artists, writers, fashion designers and so on, everyone lamented a lack of peers, a feeling of isolation in their practices. Cultivating a sense of community was also among Groundation’s desired outcomes for their arts programming. Given their focus on arts and human rights activism (particularly LGBTQ rights), I had already been thinking about Groundation in parallel with Glasgow-based Arika, which I’d visited earlier in that year (see this earlier essay for details). The team and I began looking at Arika’s Episodes and thinking about their deployment of art as “aesthetic register of sociality”. It seemed that a register of sociality—that is, a manifestation of the social possibilities generated by people talking, eating, dancing, imagining together—might be just the thing to jumpstart a new phase of programming. Additionally, the Episodes were not art object focused, instead they integrated a whole range of collaborators—deejays, writers, activists, performers etc. This seemed in line with the Groundation team’s interdisciplinary background and approach.

In one of our conversations, Malaika came up with the idea of a town hall meeting. Over a few days, we massaged that into something less formal, more like a lime. [4] We did not want to impose a structure; we wanted to make existing structures visible. We wanted to shift the focus from what was not there, to what was; tilting the axis of the conversations we’d been having. A lime—that typically Caribbean form of open-ended sociality—seemed like as good a model as any.

Initially, I did not want to do the event in a gallery: I hoped for a bar or some other non-art specific space. To get conversation going, I planned to give a brief presentation about my work and what brought me to Grenada. I wanted to experiment with doing that outside of an institutional art context, in hopes that it would help me escape an institutional style—focused on demonstration of expertise—in favour of a genuine invitation to dialogue, in line with my research interests in counter-publics, usership and so on. [5] Malaika disagreed. We’d talked about how the few galleries in Grenada did not seem geared toward Grenadians so much as to ex-pats and tourists. She thought it was more important to take possession of the gallery, reframing it as a space that could have utility for Grenadians. The idea of a gallery as an artists’ town hall also appealed, particularly after hearing Collective’s Kate Gray talk about how a visual arts organisation could position itself as a “resource” or “tool” for a city/town/island. We decided to approach Meg Conlon. She had a gallery called Art Upstairs just off the Carenage in a beautiful old building that was once a courthouse.

To keep things playful (and overheads low), Malaika hand-drew the flyers and we photocopied them on coloured paper. We shared digital versions via Instagram, Facebook and the Groundation website. We provided a few refreshments, but put a request for people to bring snacks and drinks on the flyers. I recommended the BYOB (bring your own bottle) approach as a way to invite participants to own the proceedings and take liberties in shaping them.

The first half of the event was split between my presentation and more structured group discussions around specific questions. I talked about my research interest in art within the broadest possible frame, untethered by the white cube and even the exhibition. I pointed out interesting projects across the region like Beta Local’s La Ivan Illichand Walking Seminar programmes, highlighting their sensitivity to context. I also talked about Arika’s Episodes and explained the rationale behind the Lime, making reference to the various practices I’d encountered since my arrival in Grenada and the potential I saw for collaboration and programme development. The second half was more informal, with people chatting in groups, exchanging contacts, and sharing their work. Thankfully, people drank, ate and affably interrupted the facilitators (Malaika Brooks Smith Lowe and I) and each other all throughout the proceedings.

“How am I measuring success? People had a good time, they got heated and excited, they engaged each other, and came to consider themselves a part of a group, united by a shared interest in unleashing and celebrating creative activity in Grenada. I cannot say how that will evolve, what concrete initiatives will emerge from it. I can only say that practices that may have seemed isolated and irrelevant, found themselves connected and valued.”

There were just over 30 participants, ranging in age from teenagers to people in their sixties, and it was successful enough that Groundation held another Lime shortly after my departure, this time on the beach. How am I measuring success? People had a good time, they got heated and excited, they engaged each other, and came to consider themselves a part of a group, united by a shared interest in unleashing and celebrating creative activity in Grenada. I cannot say how that will evolve, what concrete initiatives will emerge from it. I can only say that practices that may have seemed isolated and irrelevant, found themselves connected and valued. New possibilities came into view, and the revelation of new possibilities is precisely the link between creative activity and social change that Groundation seeks to activate through their programming.

We also decided to develop an online survey that would collect basic biographical and professional info on artists in Grenada. Things like the area they live in, their educational background, had they ever applied for or been granted funding? The idea came from research on the Jamaican art scenethat NLS Kingston, an experimental art space in Jamaica, first carried out in 2012. At the time, NLS was less than a year old and artist-director Deborah Anzinger had just moved back to Jamaica after living in the US for about a decade. She knew she wanted to start a space, but she wanted to be deliberate about developing programming that responded to local conditions. Sixty-four artists completed NLS’s survey, and the organisation was left with a bank of data that helped them determine their programming focus.

“In the absence of an accredited art school, a gallery system that supports regular exhibitions, or any other dedicated space for artistic experimentation and engagement; few practitioners consider themselves professional artists.”

The Groundation survey was not as successful. At time of writing only 12 artists have completed the survey and while Grenada’s population of just over 100,000 is substantially smaller than Jamaica’s approximately 2.8 million, 12 does not seem a large enough number from which to deduce anything. I think the survey could have been promoted more widely and for a longer period of time via Groundation’s social media and website, but the problem may also be with the approach. For one, the survey assumes that artists would be computer literate and have Internet access. Additionally, given the size of the population it may have been smarter to do a survey that targeted a broader category than “visual artists”, maybe “cultural producers” or “creatives”. In the absence of an accredited art school, a gallery system that supports regular exhibitions, or any other dedicated space for artistic experimentation and engagement; few practitioners consider themselves professional artists.

At the Lime for example, several people approached me to ask if their practices qualified them as “visual artists”. There were people like Jane Nurse, a textile designer with an MA in Environmental Science and a day job as a tour guide and translator, and Kenroy George who’d worked as a web developer in New York and coordinated an annual music festival in Morocco (Oasis Festival) before returning to Grenada to start an all-natural skincare line (Numad) and co-found an organisation to support entrepreneurship (GrenStart), all while sitting on the board of the Grenada National Trust. There was Neisha La Touche, a lifestyle blogger and carnival costume designer, and Vanel Cuffie, a figurative painter looking for ways to make a living from his work outside of a gallery context. Cuffie struck me as particularly enterprising, having developed an app that sells his work as smartphone wallpaper, and a line of attractive pocket tees featuring his work.

As Arika had suggested in my conversation with them, “community” could be just as confining as it was sustaining. The delineation of a discrete “artistic community” seemed inappropriate for the Grenadian context. And further, if we are working with a definition of art that is beyond the art object, should the definition of “artist” not expand as well?

All this is not to say that there aren’t artists working more conventionally, by Euro-American standards, in Grenada. Susan Mains and her son Asher for example, are both artists and they run the Art and Soul Gallery in Spiceland Mall in Grand Anse. Like Art Upstairs, Art and Soul exhibits the work of Grenadian and Grenada-based artists but in a strictly commercial sense, with less focus on the discursive potential of the exhibition format. The gallery does host several exhibitions per year however, along with regular “pop-up” events that function as mini-art fairs with booths offered to artists, rather than galleries, free of charge.

Susan Mains is also a member of the Grenada Arts Council and commissioner of the Grenada National Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Grenada has had an official pavilion at both the 2015 and 2017 Biennales. Though it is a laudable achievement, it is a bit disappointing that only two of the eight artists included in the 2017 exhibition, titled The Bridge in reference to “global dialogues,” are Grenadian: Asher Mains and Milton Williams. It is not unheard of for a national pavilion to feature artists from elsewhere, but it does attract criticism, particularly when the pavilion is that of an under-represented nation exhibiting the work of artists from nations that are well represented. A famous recent case is the 2013 and 2015 Kenyan Pavilions, which were dominated by Chinese artists. [6]

I have not seen The Bridge. I’ve seen a few images of Asher Mains’, Milton Williams’, British artist Jason deCaires Taylor’s and Brazilian Alexandre Murucci’s work, and a ten minute video on the Grenada Pavilion website provided me with some insight into Khaled Hafez (France), Rashid Al Kahlifa (Bahrain), Mahmoud Obaidi (Canada/Iraq), and Zena Assi’s (Lebanon) work. While deCaires Taylor’s installation references the underwater sculpture park he founded off the west coast of Grenada while living there, I could not detect the connection between the work of any of the other non-Grenadian artists and Grenada in particular. Curator Omar Donia’s statement describes the show as two conversations, one in “Nature and Preservation” and another in “War and Conflict”, but the link between those two conversations, and with Grenada remains obscure: “We are a tiny particle of sand in an endless sandy beach, ever changing with the vagaries of man and the environment.” [7] Reviews do not hint at those links either. Press coverage of The Bridge was dominated by the striking similarity between deCaires Taylor’s installation and British artist Damien Hirst’s blockbuster Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. [8]

The approach taken by first time Venice participants Antigua and Barbuda on the other hand, guided by art historian and collector Barbara Paca, seems a more pertinent engagement with La Biennale and the narrative of global art history that it indexes. Where the Grenadian Pavilion rings a bit hollow, the Antiguan Pavilion went with a solo exhibition of the work of seminal Antiguan artist and polymathic eccentric Frank Walter (1926 – 2009). The exhibition, which includes paintings, sculpture, audio recordings and writing, highlights the expanse that has been over-written by global art history, gesturing towards the limitations of that narrative project, rather than attempting to integrate via a dilution of difference.

Grenadian artists like Canute Caliste (1914 – 2005) and Doliver Morain (b. 1959) would be excellent subjects for this kind of art historical research and curatorial treatment. Not because Walter, Caliste and Morain could all be described as folk or “outsider” artists, but because their practices illustrate the specificity of the Caribbean context. A context in which, as art historian Veerle Poupeye has written of Jamaican art history, artists who would elsewhere be defined as outsiders have become the “ultimate cultural insiders”. [9]

There aren’t many exhibition opportunities in Grenada, and few creative producers maintain the kind of studio practice that could sustain a range of galleries, but popular art is everywhere. Projects in Trinidad like designers Kriston Chen, Agyei Archer and Debbie Estwick’s collaboration with sign painter Bruce Cayonne—using fete signs as inspiration for an indigenous Trinidadian typeface and material for a line of notebooks— are excellent models for developing projects that explore what contemporary art might mean in Grenada. Bahamian Blue Curry and Trinidadian Christopher Cozier’s curatorial project Out of Place (2016) is another model for thinking art beyond the art object and beyond the gallery. The two developed a series of “artistic actions” engaging the yard’s Port-of-Spain neighbourhood in collaboration with other artists. [10] The project sought to ask three questions:

How can we shift the encounter of visual objects or actions to more public spaces?

How can we alter or widen the way we understand the visual by dissolving received traditional boundaries between the object or action, its maker, and the viewer — untangling the idea of authorship?

How can we stage and engage the artistic process as a record of a creative or investigative action, as an experiential event available to everyone, rather than as a commodity, exclusively?

To my mind, this kind of interrogation seems more relevant to contemporary art in Grenada than a Venice Pavilion. That is not to say that a pavilion is not a worthy project. It does put Grenada on the map, so to speak, but that’s only compelling if you submit to the idea that the map (of global art) is drawn in Venice. If however, you are interested in tilting the axis, you might prefer to question the ‘meta’ of that narrative, to tease out and challenge its epistemological underpinnings. Presenting a show that functions as a disruption of that epistemology, through some art historical intervention—as I would argue the Antiguan Pavilion does—is one way to approach that. The institutional and formal interrogation of a project like Out of Place is another way to undermine an epistemological approach to art that does not accommodate Grenada’s (and much of the world’s) realities. My practice is one of identifying and generating other possible interventions in the mapping of ‘global art’ (who does it, how, why) from the perspective of the othered space, the outpost, or in Caribbean parlance those “back of God’s ear” spots.

When I met with Susan Mains she told me about the Grenada Contemporary open call and exhibition—put on by the Grenada Arts Council in partnership with the Art and Soul Gallery— from which the Grenadian artists included in The Bridge were selected. She expressed a desire for more artists to take advantage of the opportunity presented by the open call. I did not think of it then, but looking back now, I wonder if the open call does not suffer from the same problem as our survey. Perhaps the arts council should consider shaping opportunities like Venice to suit Grenada, rather than attempting to fit Grenada to Venice’s model. What might a broader call (beyond the narrow category of visual artist) leading to a presence at the Biennale—it might be interesting to think outside of the exhibition format in its strictest sense—yield? Or, an exhibition that reflects Grenada’s rich popular art traditions or engages its still contentious and unfolding political history—another indication of the significance of grassroots agency and popular activism within the Grenadian imaginary.

For my part, during my visit I could not stop imagining a grand public art-popular painting street festival. If the government donates paint to the communities every Independence, what would a semi-structured collaboration between the island’s sign-painters, muralists, designers etc etc and these neighbourhoods look like? It’s a simple idea; just a deliberate zeroing in on a practice that is already widespread. It could be an on-going programme, anchored with events that might evolve into a kind of street festival celebrating local creatives. Let me be clear, these imaginings are not to be understood as a prescription. They are merely imaginings, voiced (in this text, at the Lime and in multiple one-on-one conversations with Grenadian creative producers) more as a question, a kind of conversation prompt than anything. Because, like the sound of kites, I’m not terribly familiar and I don’t have to live with it.

My hope is that having initiated those conversations, with Groundation and the broader community, I will have supported my host organisation and other Grenadian creatives in developing a genuinely home-grown approach to arts organising.